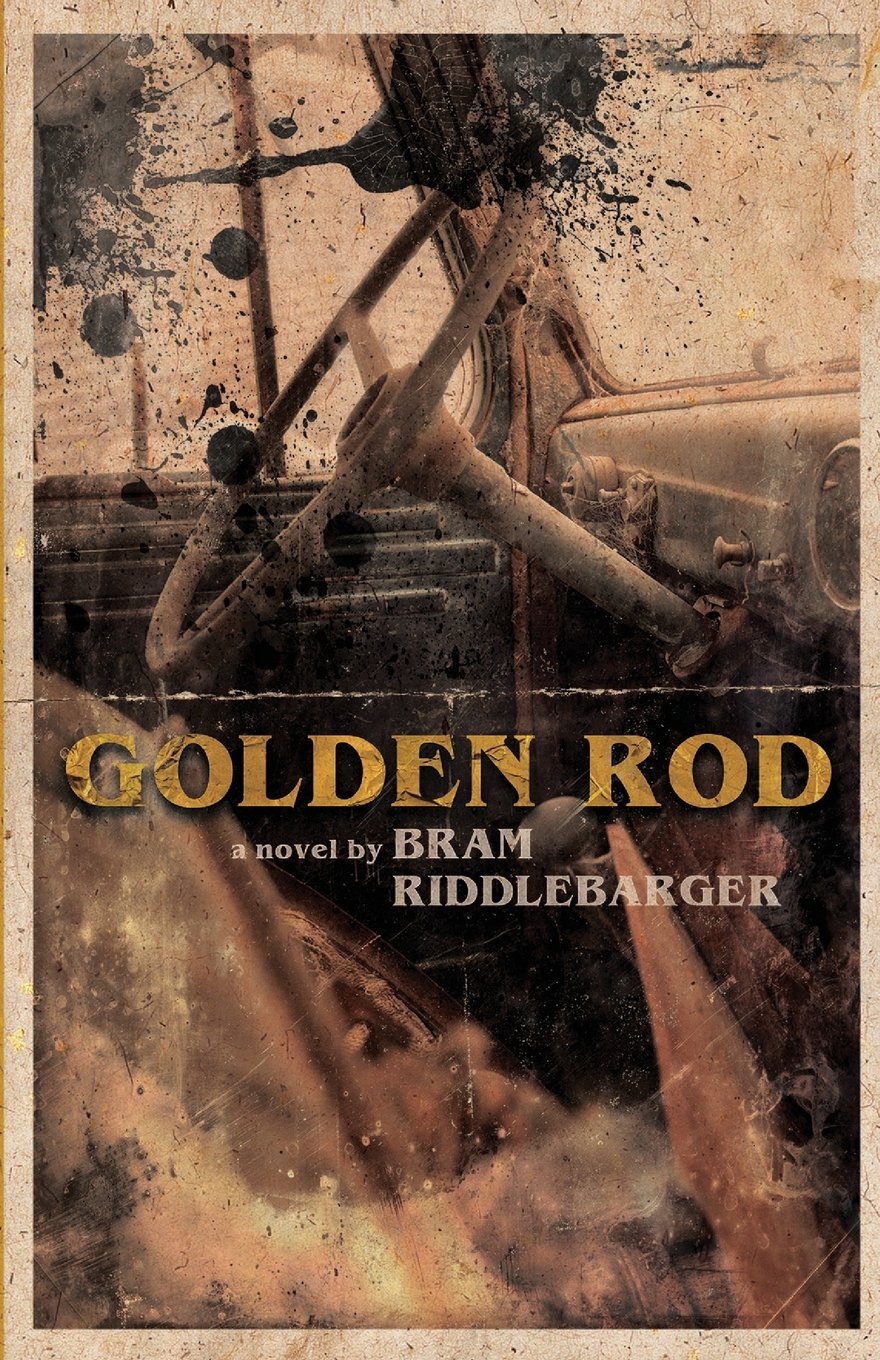

Bram Riddlebarger is the author of the novel Earplugs (Livingston Press, 2012) and a poetry chapbook, Chez Filthy (JKPublishing, 2009). His second novel, Golden Rod, was published through Cabal Books. He has also published short fiction and poetry in a series of engaging venues such as Tyrant Books, X-R-A-Y-, New World Writing, and The Cabinet of Heed.

I have had a weekend now to ruminate over Golden Rod and still don’t feel that I have properly compartmentalized all the book offers. Perhaps this is because of it’s wild and absurd nature. Goldenrod could be described as an organized chaos that could be described as a philosophical study of both individual characters and larger facets of society as a whole; such as materialism, the power of folk lore, compulsive behavior, and corruption as it surfaces in members of authority. The character range of this novels spans from Merle Haggard, who is immediately placed as the soundtrack of the novel, to a political revolutionary, to the ghost of a dog. With this incredible spread, Riddlebarger is able to show how these caricatures of personalities and stereotypes interact with each other in an often comedic or satirical, but simultaneously honest and revealing, way.

The novel follows a central character, Jack, as he attempts to maintain a lifestyle despite the world around him crumbling. He loses the shack he was living in, purposefully sets his truck on fire, ends up in a mental institution, and eventually transitions to living in a cave with The Revolutionary who befriended Jack’s dog, Sid, while Jack was institutionalized. This is where the central theme of the novel lies, as The Revolutionary says himself, “What we seek is a return to the pagan- to the hills -to a life without cars.”

A large part of what makes this novel so engaging is the world built within it. It isn’t sheerly fantastical, though it does have some fantastical elements, such as vulgar fairies and an ancient monster trapped beneath the Earth’s crust. A large majority of the world is identical to ours. Society exists the same as it does now for you and I, authorities figures exist and people grocery shop and visit tourist attractions, but Riddlebarger describes it through an almost minimalist lens. For example, authority figures are simply referred to as the Law or Rangers One to Four. They don’t require names because their whole character is defined by their actions, dialogue, and job title. The same goes for almost the entire cast of characters, many of whom sport no name or a strange nickname: Hippie Girl, The Rock’nRollers, The Silent Ethiopian, and The Revolutionary are all characters who are defined by a personality trait, be it a world view or political ideology, and not much else. The Revolutionary wants to wage war on capitalism and Hippie Girl wants to smoke her pot.

Jack just wants to sip tea.

Miracles occur, characters are spoken into existence, bizarre things (like a large number of tourists plummeting from a cliff and shattering into dust or a talking gun deciding to come out of the closet) happen and no character bats an eye because that’s just the world they’re living in.

Sounds familiar, right?

The cave where Jack and The Revolutionary live accumulates a large number of characters with quirks and faults and human desires. They band together in an attempt to survive in the wild despite being predominantly modern folk. They harvest acorns, try to hunt deer with rocks, and shower in a public waterfall. While this cast remains starving, staying alive due to drinking tea and eating foraged nuts, the world outside idly coasts by with comforts in hand, completely ignorant to said struggle; customers continue shopping and tourists continue taking photographs of waterfalls. The group’s actions reach an inevitable conclusion that suggests the pagan life is an impossibility in a modern world. We can yearn to return to it but we are very possibly too far gone. The world doesn’t want us to live in a cave anymore, even if it makes us happy. The world wants us to obey the rules and play the game as it has been designed by the hands of Big Money.

Golden Rod comments on several topics and types of people in rapid succession. It is a fast paced romp through the strangest reflection of our world that I have yet to witness. It is a book that will urge you to contemplate necessity, companionship, and the face value of all you encounter. Finally, it’s funny. There are scenes like when the group goes on strike within a grocery store by chaining themselves to produce stands and shouting at the customers to buy local produce instead, but nobody pays attention to them at all and their efforts go entirely unnoticed, that are outrageous but also realistic. For the most part, I think we would ignore some dirty vagabond tied to an avocado stand shouting at us.

The absurdity and coupled humor of Golden Rod is comforting in the sense that it makes our incredibly bizarre state of affairs in 2018, from social to political to artistic perspectives, seem somehow more bearable compared to the exaggerated world Riddlebarger has created. The novel highlights the idea that we are drifting further and further from the caves in which our species once lived, and whether that’s good or bad, perhaps a bit of both, is up to you. Golden Rod reminds the reader that anything is possible, that folklore might be built on fact, and as a reader I find that idea incredibly empowering. In this day of abstract and symbolic thought, where humanity is on the cusp of a social revolution and we are careening into a tunnel of change, Riddlebarger reminds us of who we once were and who we are capable of being.

—

Cavin Bryce is a twenty-one year old student of English attending the University of Central Florida. He spends his time off sitting on the back porch, sipping sweet tea and watching his hound dog dig holes across a dilapidated yard. His work has been published in Hobart, CHEAP POP, OCCULUM, and elsewhere. He tweets at @cavinbryce.

Naturally, we had a few follow-up questions for Bram:

BRYCE: Obligatory question: do you like tea? Tea is all Jack wants or needs and every other character has a drink of their own as well. Both in and out of context of the novel, tell me what your relationship with tea is like.

RIDDLEBARGER: Coffee in the morning, tea in the afternoon, beer in the evening. Of course, there are many varieties of each, and I’ve found that I enjoy trying as many of each of them as I can, unlike the characters in the book, who tend to be locked into their preferred substances. To change brings further change or a metamorphosis, which can of course bring one joy or pain. The book also reflects Plato’s “Allegory of a Cave” quite a bit so the themes, names, characters all rely quite a lot on the Platonic Ideals, of which tea is one. Of course, food and what we consume or don’t eat also plays a big part in the book, too.

BRYCE: Sid the dog seems entirely motivated by his own desires as opposed to the typical master – dog dynamic. Sid has his own idea of comfort just as much as any other character and his allegiance is based off what he can gain. Was he modeled after an idea you have of dogs or a specific animal you have known in your life?

RIDDLEBARGER: Sid is somewhat of an amalgam of all the dogs I’ve known. I like animals in general, but I love dogs. The book is dedicated to my dog Pretty Girl, who also appears in the author photo at the end of the book by the gravestone of the author Don Robertson. He’s buried in my hometown, within sight of the house I grew up in. I love his book Paradise Falls, from which I took a quote for the epigraph. I thought it was a fun way to bookend bookends and also honor two animals that significantly helped me write the book. I also firmly believe that all animals, even domesticated ones, still have their own cultures and thoughts, rituals and desires, which human animals too often ignore. There is no separation of the wild and the domesticated or tamed really. That separation is a construct of human teaching, thought, and naming. The reality is just this world that we all live in. Again, food comes into play in a big way there.

BRYCE: The idea that legends, both of monsters and vagabond groups alike, can move people and generate so much conversation on a town scale was really interestingly explored in Golden Rod. Are there any local myths or legends that you can recall? Where do you feel the power of these myths comes from?

RIDDLEBARGER: Well, locally, the Mothman legend for sure, which I reference a few times in the book. That supposedly happened in Point Pleasant, West Virginia, which is actually very close to where I live in southeastern Ohio. Athens, where I live now, is considered to be a very haunted place for various reasons by many in the occult business. There is an old sanitarium here overlooking the town, called The Ridges now, but was once the Athens Lunatic Asylum. It is very grand. It was practically a self-sustaining place during its heyday. For years, it sat largely empty and people would sometimes break in and everything was quite eerie. There are many famous stories about it. I believe I even had a relative committed there once. Ohio University has since restored it and now uses it for facilities. This is also an area that once had many burial mounds, most of which have been destroyed, but there are still some left. We live on the remains of these mounds around here, which is a sobering thought, I think. The book alludes to this. I also drew on the fracking that threatens to overtake the area, as it has in other areas close by and elsewhere. This part of the country, like many Appalachian places, has been exploited for resources for centuries. Fracking and tourism seem to be highest on that list at the moment around here, although I suspect sand will continue to climb on that list. Myths grow from these things. Exploits, quests, the good and the evil. Nature and humankind. Nietzsche and Joseph Campbell stuff filtered through the lens of my earlier comment that this world is just one place, it’s not black and white, and we construct these stories. But rather than a creation myth, this book tends to be more of a destruction myth, and the hero more of a confused hero/anti-hero.

BRYCE: The novel often bounces around town chapter by chapter in that it will change settings and characters rapidly. You could be in a diner with The Rangers one chapter and then on a mound in the forest with Jack and The Revolutionary the next. How did you decide to balance these chapters? Did you have a cast of characters before you started writing that you wanted to include or did you generate some along the way?

RIDDLEBARGER: I had most of the characters cast early on. I think I added the hygienist a bit later, which may be somewhat obvious, but she became a necessary character for a number of reasons. Again, the Allegory of the Cave plays a part to some degree, with an accompanying set of characteristics for each. I had to have the coffee drinkers, the beer drinkers, etc. As for the chapters, the only real balancing change that I consciously made was the opening chapter, which is a time shift. The book was pretty linear for me in the early drafts, and I think altering the opening chapter helped the narrative.

BRYCE: Who was your favorite character to write for? Or, alternatively, the scene you had the most fun writing?

RIDDLEBARGER: I had a lot of fun writing most of these characters. The Wood Fairies were fun just because they are such assholes. The Revolutionary was most often the focus as the de facto leader of the cave and also the mouthpiece of their failed cause. But I think each character gets their moments, and I very much enjoyed writing for each of them, especially when it was their time to shine, including the Rangers and the Law. I had the most fun then, especially when it was funny. Like when the hygienist wants to make a break for Oral Care, for example. The grocery store scene in general was pretty fun to write. I’m a huge fan of grocery stores. I can walk the aisles of most any food store for much longer than most people would deem appropriate. If I travel, grocery stores are one of the places I have to see. It’s like an anthropological dig with price tags. And often an accompanying soundtrack. Foodways are a key part of the book and something that I’m very interested in to the point of obsession.

BRYCE: Are there any projects you’re currently working on that you’d like to talk about?

RIDDLEBARGER: I have two novels in early stages. I’ve been working on some short stories with the aim of getting a collection together within a year or so. I mainly write a lot of very short fiction and poems, which for me generate ideas that can become cohesive over time. I have quite a number of short prose and poetry collections that I’d like to publish someday either independently or collected together. One collection of poems in particular, Western Erotica Ho, I’d really like to see published. I’ve had it close several times, and things didn’t work out, but I think it’s strong enough to stand up by itself. In the meantime, I’ll keep submitting work to various places. I almost have enough poems ready for another small collection. I write best over the winter, so I expect to make a lot of headway on one of the novels and the short stories soon, although I have some idea that they may morph together into some other strange thing, but the way has not yet revealed itself and perhaps it won’t.

Golden Rod was published by Cabal Books and is available through Amazon and other online markets.