Last spring, when I begun to realize my relationship at the time was slowly breaking apart, I told my then-lover I still had hope for the future.

It was the middle of May 2020, and we were sitting on the couch in the house I was renting. He was looking out the window. I was looking at him.

“I don’t have that kind of hope,” he said. “I have to live as if the system is broken.”

It broke me a little too to hear him say it. It wasn’t just the deadness, the sadness, in his voice, the sense that with each word he was moving farther and farther away from me. It was the suggestion—perhaps his, perhaps just my own internalized fear—that I was both privileged and foolish to be hopeful in the face of the disaster we were living.

Unfortunately, in some ways I was right. At the end of May, my then-lover went back across the country and back to his life, and after that, we no longer talked about building a future together, although the breakup—prolonged and protracted because of distance and pandemic pressures and avoidance of the truth[JT1] [MOU2] that the relationship was not sustainable—came months later. At the end of May, George Floyd was murdered and the protests began; two nights after my then-lover went home, I stood in my backyard and listened to the gunshots that killed David McAtee just ten blocks from my house. My lover at the time was right too: I was privileged and foolish. But it wasn’t because I was hopeful. It was because I was safe and secure in so many ways others were not. It was because I had also believed until 2016 that the system was broken, and broken implies that somehow it can be fixed. But in 2016, I began to suspect that something else was going on, and I wished I had recognized it earlier. By the summer of 2020, I understood that the system was working exactly as designed.

In her book We Do This ‘Til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing And Transforming Justice, Mariame Kaba writes that we have to reject ideas that policing and the criminal justice system are broken because “reform is reaffirmed and abolition is painted as unrealistic and unworkable.” Although Kaba is speaking specifically about our country’s systems of punishment and incarceration, her words are applicable to so many of the systems and institutions in the United States, so much of day-to-day life here, in fact, because so much of life in the United States is ingrained with a carceral mindset. From education to religion to work to marriage, we are directed to follow the rules, to obey, to accept, to never challenge the foundation of these institutions under threat of consequences, specifically shame and ostracism and outright punishment by a national culture that upholds the cishet white heteropatriarchy as the pinnacle of power and authority.

But change will never come by accepting the status quo or by living our lives as if the system is broken. Change comes instead, notes Kaba, by recognizing that injustice and inequality are built into the system and that the only way we move forward is to dismantle the old system and build a new system – one that’s focused on transformative justice and that builds community and an equitable future through daily actions. And that, notes Kaba, is where hope comes in. Hope, she says, is not an emotion or optimism. Instead, she says, it’s a discipline, a “grounded hope that (is) practiced every day.” It’s easy, says Kaba, to feel hopelessness. “I just choose differently,” she says.

These days, I choose differently too. That doesn’t mean that my privilege or foolishness is absolved; in fact, I am even more aware of its constancy. This awareness is part of my daily practice of hope: of knowing I will fuck up but believing I can do the work to rectify my mistakes and to learn not to repeat them, of seeing community and the future as something I can help to build each day. And hope I do, even though for months now, I’ve been writing about the range of emotions we’ve been experiencing as a result of this pandemic and the system failures that continue to devastate the most vulnerable people in this country and press the weight of bearing up on the backs of caregivers. I’ve written about how governmental incompetence has impacted caregiver lives and how devastating the pandemic has been on caregivers. I’ve been writing about how people, primarily women, have given up their careers and their identities to care for children and disabled folks and the elderly because every system that was supposed to support us has left us to deal with this on our own.

I’ve also written a lot about how many of the caregiver stories that end up in U.S. archives center the lives of cis, white, middle class, able-bodied women and how I wanted this column and this caregiver archive to focus on something different: the stories of Indigenous, Black, and other caregivers of color; disabled caregivers; undocumented caregivers; queer caregivers; and working class and low-income caregivers that are so often left out.

In the six months I’ve been gathering and researching these stories, I’ve learned many of them fall into at least one of four categories of emotional response: rage, lust (or lack thereof), grief, or isolation and loneliness, and I’ve spent months diving into caregivers’ experiences with these emotions. And now, in this final column, I’m returning to the last of those caregivers I interviewed to see where they are now and to see what has changed, to see where the little glimmers of hope arise, and to articulate this project’s futurity.

I first interviewed 24-year-old Macey Spensley several months ago, when she told me about how she and her 27-year-old boyfriend were both coping with Type-1 diabetes in the pandemic.

When we first spoke, the situation was frightening: Macey’s boyfriend was struggling with low blood sugars, and they were both grappling with fear as well as the loneliness that comes with constant caregiving.

Now, said Macey, things have stabilized somewhat because of her boyfriend’s glucose monitor, which he received in February 2021. When we first spoke, she said she was still “waking up in a panic” every time he moved because she was afraid he was in danger, despite the monitor.

But now, said Macey, “every time I hear that beep in the middle of the night, no matter how tired I am, I’m so thankful. That beep is saving his life. I still find myself getting nervous when he’s moving a little too much in his sleep, but at least I know we can catch any dangerous low blood sugar a little bit sooner.”

The hardest adjustment, said Macey, is “I now have easier access to knowing his blood sugars during the day. He gets frustrated if I ask too much. I have to do better at respecting his boundaries and knowing he knows how to take care of himself.”

But for her, caring for her boyfriend is also about balance. “For me, loving him means both worrying about him and knowing how strong he is,” she said. “This technology that we are so incredibly privileged to have, especially since he kept his grocery store job throughout the pandemic and didn’t lose health insurance, has made everything so much easier to digest.”

When I returned to Anonymous, 27, in the greater New York metropolitan area, her life and her guardianship duties for her mother were a mix of stress and hope.

“My workload has increased,” she said. “One of my jobs offered me a full-time position.”

Anonymous said that while it would be great to have steady income, “I worry about how I will be able to do that and attend to my guardianship duties. My mom’s properties were supposed to close earlier this month…but it has been one headache after another…I have to chase a lot of records around.”

In addition, said Anonymous, her annual guardianship report is coming up soon, which will require an accounting of all she did for her mom in the past year. “I’m definitely feeling a little overwhelmed at the moment,” she said.

Finally, Anonymous noted that her emotional wellness is also still in flux.

“I had a difficult day today,” she said. “Even though I’m in therapy, there are so many emotions I don’t express to (my mom), and there are so many emotions I still push down. They’ve been overflowing a little bit this weekend.”

Although she’s still processing and coping with certain aspects of guardianship, and even though the pandemic continues, Anonymous notes that things are improving in her life.

“I can see my mother whenever I want now!” she said. “I can hug her! I’m hoping that I can find someone to date and spend time with. In the back of my mind, I hope I can be with the person I truly long for in the near future. I hope I find the courage to come out as queer, such that I can actually manifest those desires. I just want to be my full self, without pushing anything down.”

Finally, I also returned to speak with Anonymous, 32, in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, who told me about a recurring pandemic dream she’d had about her second book launch. Since her childcare returned in July 2020 and since getting both herself and her husband vaccinated, she said, some things in her life have eased. But, she said, because her four-and-a-half-year-old is not vaccinated yet, situations arise that still make life difficult.

One recent difficulty occurred when she fractured her ankle and had to go record a podcast episode. Because she wasn’t able to drive, her husband had to take her. It shouldn’t have been a problem, she said, “except we learned on that 90-degree day that his AC in his car wasn’t working. And now he was stuck with our small child where they could only be outside (he had planned to have a picnic in a park) with no AC in the car to return to if anyone got too hot.”

The situation ended up being fine, said Anonymous, “but we had a moment of: how are we supposed to do these things safely? In any other year he could have slipped into Target in the AC and wandered around until they both cooled off. But not this year. Or last.”

Just navigating life with a fractured ankle has proven to be increasingly difficult in the pandemic, she noted. Her husband has taken over a lot of her responsibilities, but she’s limited in mobility and in where she can go.

“Now I feel doubly trapped, or perhaps trapped all over again,” she said.

All in all, however, said Anonymous, she still feels a mixture of emotions. “I am so lucky. I have so much support. I am so tired and sad. So much feels like a bruise that any new obstacle feels like pressing a thumb squarely into that bruise and asking, “Does that hurt?” Yes, it does,” she said.

The stories I’ve been charting for six months are all so different, but one thing is constant: there are small glimmers of hope. Even in this small sample set of caregiver stories I’ve gathered so far, I can see the beginnings of a constellation. And that is why, now that the column is over, I’ll be switching gears to begin construction of the Submerged Archive digital platform. I’m eager to build this community, this future, this constellation of stories with their pain and their hope, to give people a place to bring their stories when they need someone to remember what they’ve been through. And of course, even though the column won’t continue, I will still continue to tell you, my readers, about how this project is coming together.

Nearly a year and a half into this pandemic, and six months in to this project, we are still submerged. We are still raging. We are still grieving, still longing, still alone. We are still here. And so many of us are still hopeful, too, because hope is one of the only things we have left to practice when so much has been taken from us. That, and love.

Here is to the daily practice of building this archival storytelling community. Here is to the future, to this daily practice of hope. May it continue for us all.

I, for one, am just getting started.

The interview with Macey Spensley took place via email on June 28, 2021. The interview with Anonymous, 27, of the greater New York metropolitan area took place on May 23, 2021. The interview with Anonymous, 32, of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania took place on May 25, 2021.

All identities of caregivers who choose to remain anonymous for the purposes of this column or the archive are recorded but will be kept confidential in archive records.

For more information on the larger archive project, please visit the Patreon for Submerged: An Archive of Caregivers Underwater. If you have a story to tell that you think should be included in the archive, stay tuned — the archive will be up and running in a few months!

—

Web: submergedarchive.com

Twitter: @wearesubmerged

Patreon: submergedarchive

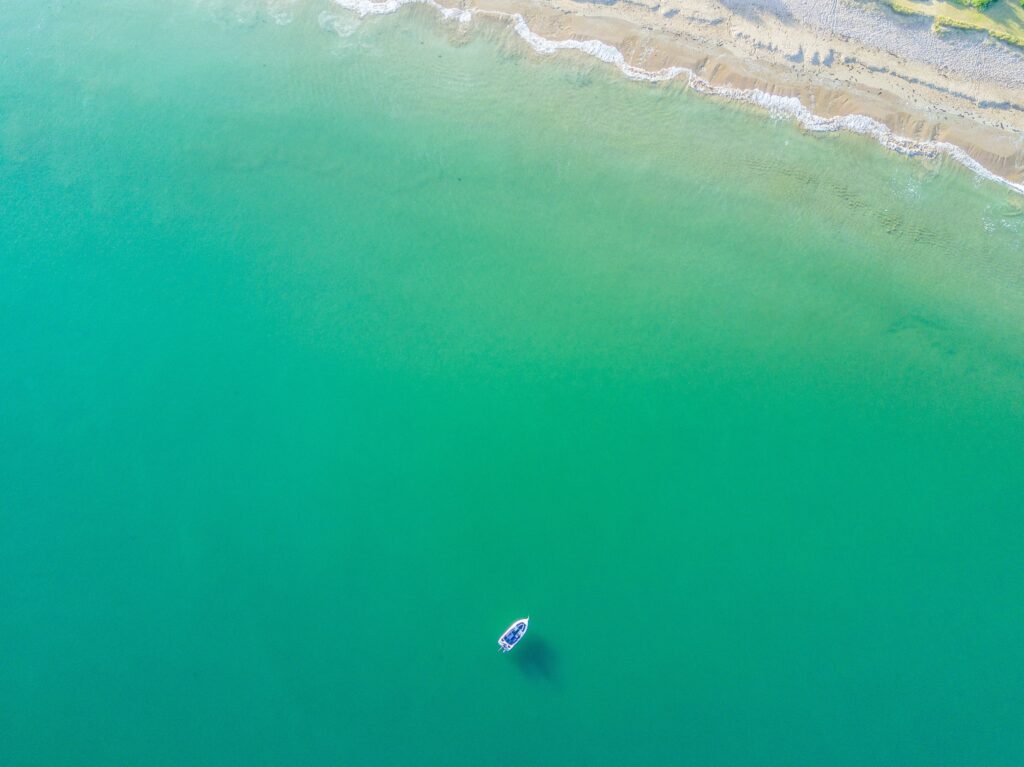

Photography by: Rod Long