I rubbed the flecks of white stubble on my chin as I sat at my desk at work, longing for the day I wouldn’t have to drag myself into the office every morning—if that day would ever come. My mind entangled itself in my current invention—not much of an invention at that. I always fancied myself an inventor. When I was a little bucktoothed kid and people asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I’d squeak, “An inventor!”

But an inventor’s not an easy thing to just become (hence my job running assessment reports). Almost everything’s already been invented—to my tiny brain at least. I never manage to come up with sweeping visionary ideas, just tinker with what’s already been done, try to improve. I guess I’m a tinkerer more than an inventor, but no one will pay me to sit and tinker all day, thus I’m stuck here in the suffocating false-light of this office.

I have this book only because a friend didn’t want it–even though this book could save my life. You don’t need a plot to tell a story, obviously. When I admired it on his shelf, he said, “Go ahead—take it. I don’t want it. He’d said the same thing moments earlier when I admired the green tea ginger ale in his fridge.

Don’t trouble yourself with wondering how which words appeared where when. Let’s just say there’s a certain magic to these things. I only have the shredded memory of best thing I ever invented. If I recall correctly (which of course, I may not), I conceived of the idea and explained it to a neuroscientist I had been acquainted with at a conference. It was exactly in line with the sort of work he’d been doing—isolating memories—and I think he was the only one in the world who could have done it.

In my marketing materials, it says:

Re-read your favorite book.

For the very first time.

Few people knew about the invention other than ourselves and our families. When his son defeated the purpose of the machine by turning himself tabula rasa, the neuroscientist forced us to forget how the machine was made. He could probably figure it out again if he ever wanted to.

What amazes me is not only the fact that there’s so much out there in the world created by humans, but that every day, often before dawn, they wake up out of their warm beds, leave their families, and board busses, trains, cars, and planes in an effort to keep this massive society moving, functioning, and expanding.

Of course, my best extant invention was actually invented by Jorge Luis Borges—he was far ahead of his time—of course. He created a Library of Babel. Jeff Marsh created an Espresso Book Machine. Coca-Cola invented the Freestyle Coca-Cola Machine. I’m a tweaker, I told you. I invented the Flavor Your Own Book Machine.

Just imagine how many times this same exact conversation is happening every day:

“Hey, how’s it going?”

“Oh, I can’t complain. It wouldn’t do any good anyway!”

It must be happening hundreds of thousands of times every day. I’m counting slight variations, of course. Every second, two people are saying, “I can’t complain. You wouldn’t listen anyway!” and guffawing in the camaraderie of acquaintances stuck at work together.

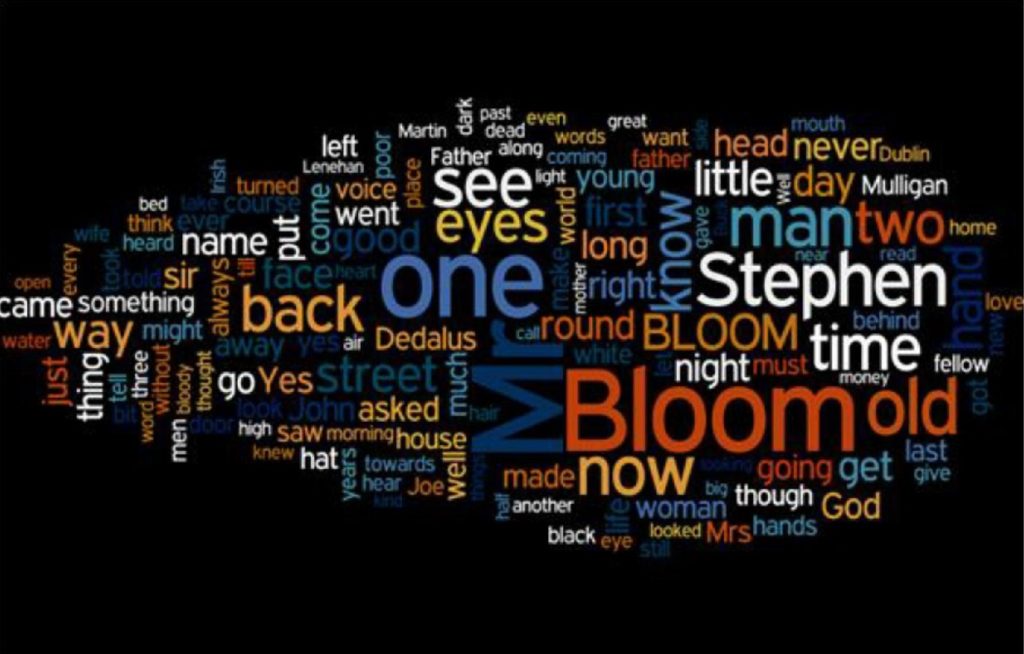

I’m sure the technology existed since word processing became standard. A basic example being the Wordle. See, here are the most frequent words, common prepositions/articles, etc. omitted, in Ulysses:

[editor’s note: Happy belated Bloomsday!]

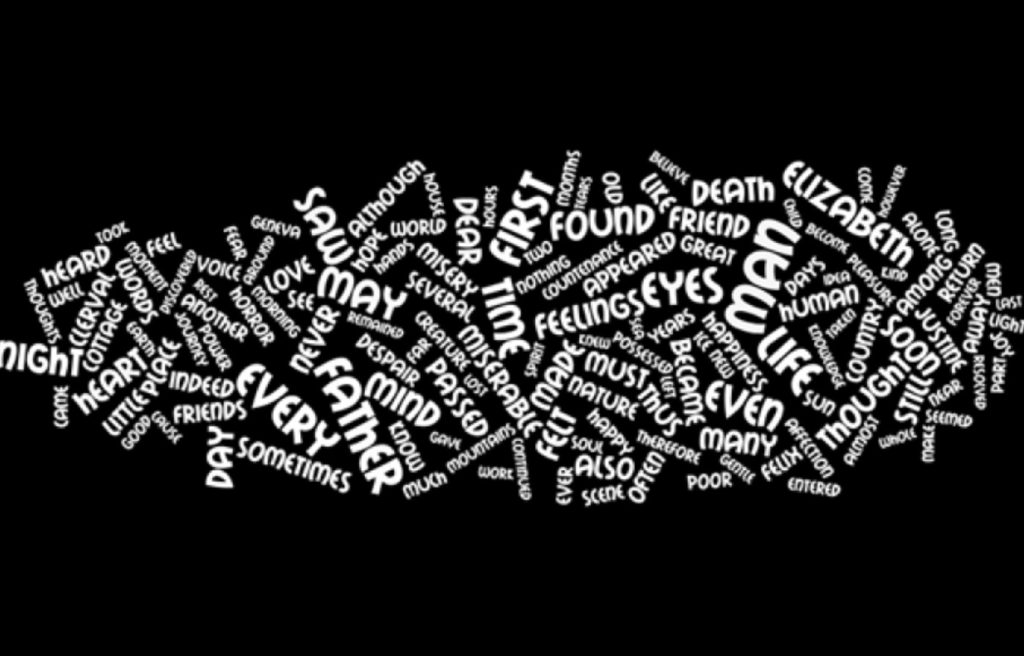

Or here’s Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason:

And here’s Shelley’s Frankenstein:

Now this is basic, just running a report to isolate the most frequent words, and enlarging the most common ones. However, imagine if you expanded this technology to deal with millions of words, phrases, sentences, and paragraphs—tagging them into categories, and rearranging them into books?

See, my invention works like the Coke machine. First you choose caffeinated or non-caffeinated beverages—say, Literary, Mystery, or Sci-Fi/Fantasy—then put in your flavor—lime, cherry, vanilla, etc.—say humorous, tragic, philosophical, etc. But when you’d already be sipping a bubbly soda, you’d still be inputting your book preferences. And—voila!

Over a hundred combinations of soda may be impressive. But we’re nearing an infinite number of books.

As I approached the square on my way home, I caught a glimpse of my reflection in a storefront. In my full suit, but with long hair, a beard, and a big camping backpack, I looked kind of cool and mysterious. But inside, I felt lost and defeated.

Who knows what you put in to get this—

—

Joseph Patrick Pascale’s work has been published in Birkensnake, Literary Orphans, Full-Stop, 365 Tomorrows, Off the Rocks, Instigatorzine, The Apeiron Review, Seven by Twenty, and On a Narrow Windowsill: Fiction and Poetry Folded onto Twitter, among other journals and anthologies. Pascale studied under poet Mark Doty when he earned his master’s degree in literature from Centenary College. He worked as a farmhand, reporter, auto parts deliverer, and reference book editor before becoming educator, and he currently oversees a writing center at an urban community college. His website is www.josephpatrickpascale.com.