Zora and I take the cab downtown to see the five o’clock matinee. This part of town is a dead spot at this time of day—too late for the morning people to show up and too early for nightbirds to care about. Zora is all jittery, swiping away at her phone during the whole ride. I’m busy giving directions to the driver. The tumor on the side of his face is the largest I’ve seen in a long while, only a finger shorter than his head and purple like a bruised fruit. I don’t say anything about it, it’s beyond helpless at this point. There’s no saving him. It. In the papers I read more and more about people like him lately, those who live with tumors the size of a limb, a child, befriending an outgrown enemy.

When the doors of the theater slide open, the warm air inside pours out and washes over my glasses with its steam; everyone inside looks equally ugly behind the blurry globe, tumors or no tumors. Zora heads over to the popcorn stand, which leaves me hanging by the lifesize cutout of the actors we came here to see. The cashier has the beginning of a tumor that blooms out of the corner of her lips, suspending her words like a speech balloon. She can feel my gaze on her, careful to engage in eye contact with Zora the whole time they chat. I can hear her speaking of her tumor like a separate entity, like a second shadow that wouldn’t let go. Sheeesh. Ieeeesh. Pom. There she creates a new grammar with three words and two pronouns—one for herself, the other for it / its. She talks and talks. The punchline is that there are so many things she’d like to do with her life, now that her life is practically over thanks to this unexpected growth. With each new word, she dies over and over in her little moment, in her beautiful ugliness. I can’t decide whether she or her tumor is harder to look away from. Is it the egg or the chicken?

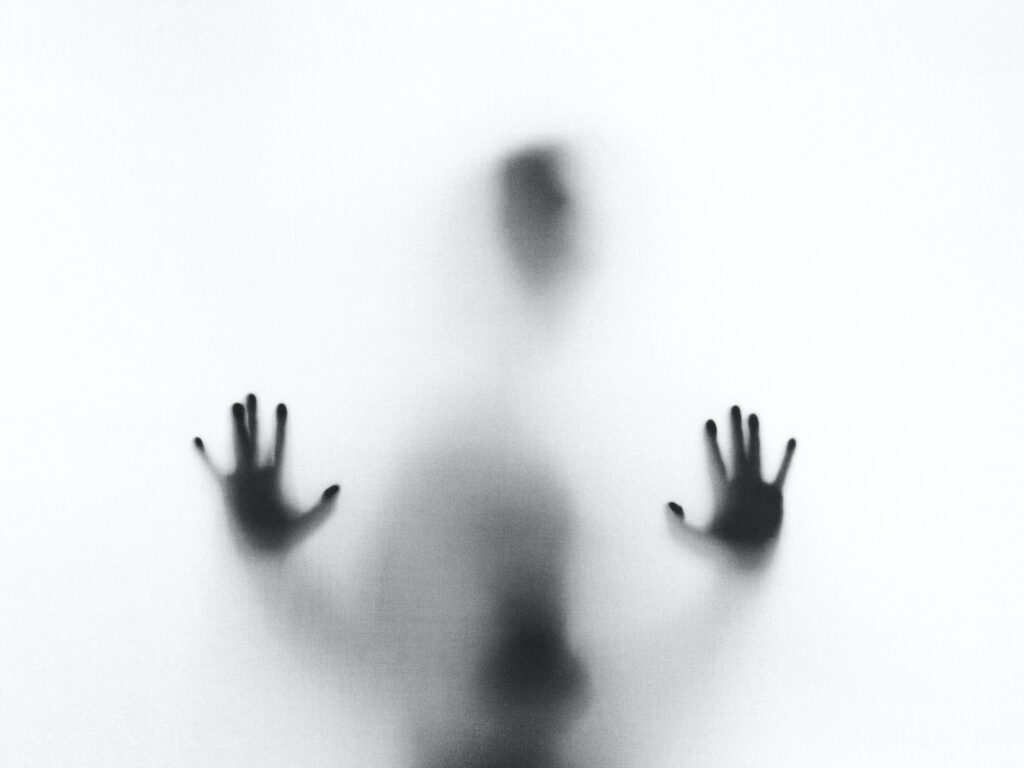

Once inside, Zora scoops the better seat. The rows are full of tumorous people, the older kind scorning the new. They giggle. They fight. The actress on the screen tells someone offscreen to shut up. Zora’s face assumes an otherworldly quality bathed in the technicolor light of a sex scene, her cheeks bright with wonder. All those words passing over her eyes, the actor’s fist-sized cheek tumor superimposed on her face, warning me of something I can’t at once decipher. As she shoots palmfuls of popcorn into her mouth, I can’t help but watch the mole to the side of her nose take countless many shapes like some ghosts in the pandora’s box. In the half-dark of the movie theater, I can’t tell if it has grown slightly larger than before. I can’t tell if my love would be enough to save her if it did. I can’t tell if I would love her, still. I can’t tell if it’s my lips or hers that quaver with horror, or both. I can’t tell if anything about her is original anymore, her complexion, her chin, her heart, each painted in one color after the other. One color after the other.

—

A YDW fellow, Sarp Sozdinler’s work has been published in the Kenyon Review, Masters Review, Normal School, Maudlin House, Hobart, HAD, No Contact, X-R-A-Y, among other places. Some of his fiction pieces have been anthologized and received a mention at literary events, including the 2022 Los Angeles Review Flash Fiction Award and the Waasnode Short Fiction prize selected by Jonathan Escoffery. He works on his first novel in Philadelphia and Amsterdam. You can follow him on @sarpsozdinler and read his work at www.sarpsozdinler.com

Photography by: Stefano Pollio