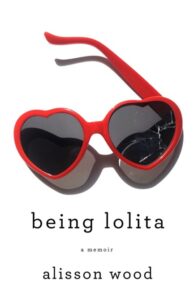

Alisson Wood’s writing has been published in the New York Times, The Paris Review, The Rumpus, Catapult, and No Tokens Magazine. Alisson teaches creative writing at New York University and at Sackett Street Writers’ Workshop. She is the founder and Editor in Chief of Pigeon Pages, a NYC literary journal and reading series. Alisson was a winner of the inaugural Breakout 8 Award from Epiphany Magazine and Author’s Guild. You can find her on Twitter at @LiteraryTSwift and on Instagram at @AlissonWood. Being Lolita, from Flatiron Books at Macmillan, is her first book.

Leonora Desar’s writing has appeared or is forthcoming in River Styx, Passages North, Black Warrior Review Online, Mid-American Review, SmokeLong Quarterly, Hobart, and Quarter After Eight, among others. She won third place in River Styx’s microfiction contest, and was a runner-up/finalist in Quarter After Eight’s Robert J. DeMott Short Prose contest, judged by Stuart Dybek. She writes a column for New Flash Fiction Review—DEAR LEO. She avoids writing @LeonoraDesar and by fiddling with www.leonoradesar.com.

Alisson Wood’s writing has been published in the New York Times, The Paris Review, The Rumpus, Catapult, and No Tokens Magazine. Alisson teaches creative writing at New York University and at Sackett Street Writers’ Workshop. She is the founder and Editor in Chief of Pigeon Pages, a NYC literary journal and reading series. Alisson was a winner of the inaugural Breakout 8 Award from Epiphany Magazine and Author’s Guild. You can find her on Twitter at @LiteraryTSwift and on Instagram at @AlissonWood. Being Lolita, from Flatiron Books at Macmillan, is her first book.

Leonora Desar’s writing has appeared or is forthcoming in River Styx, Passages North, Black Warrior Review Online, Mid-American Review, SmokeLong Quarterly, Hobart, and Quarter After Eight, among others. She won third place in River Styx’s microfiction contest, and was a runner-up/finalist in Quarter After Eight’s Robert J. DeMott Short Prose contest, judged by Stuart Dybek. She writes a column for New Flash Fiction Review—DEAR LEO. She avoids writing @LeonoraDesar and by fiddling with www.leonoradesar.com.