I woke to the thrumming of rain, remembering you had left the window down in the van. The morning sky was a gray rim above the sheet sagging across your window. Beside your bed, on the antique walnut nightstand your great aunt left you last year, a vase of pale red roses. I stood and looked for my jeans.

“Where are you going?”

“The van.” It was awkward being naked in the wan morning light. The feeling surprised me.

“Come back to me first,” you said. Your knees moved apart beneath the weight of the flannel sheet. I pulled on my jeans. Your knees slid back together.

“What happened to us?” you said.

“We were struck down by the unsettling of our roses.” Maybe I heard it somewhere. I don’t know. It was a strange thing to say, but it was too late to unsay it.

The street was deserted with the first rain of the season. Beside the van, a finite but uncountable number of shards like sea glass. The passenger window halfway down, and still they broke the rear side window. An old man trudged by with a tired umbrella. “Assholes,” he muttered. My guitar was gone, but they’d left my sketch book. It was soaked, the pages curling like eucalyptus bark.

When I got back to your apartment, the shower was running. The roses looked broken in the cheap white vase, stems bent across the edge, petals slouching toward the dingy carpet.

“Are you back?” you called, voice rising above the hiss of the water. “Are you there?” I walked into the kitchen without answering. Through the window, I watched the rain spatter the roof of my van. I tried to focus on every tiny collision.

You were singing. The melody reminded me of “Strange Fruit,” although I was pretty sure you’d never heard it before. I pictured your long fingers combing conditioner through your hair, nails bitten to the quick. A young girl with a rolling suitcase stopped to peer through the broken window of my van. She looked around, and then she moved on. I closed my eyes and swayed to the sound of your voice and the landing rain. The edges of the world felt softer for a moment.

I recalled a story you’d told me about your father. With your head pressed against his chest, you asked him about the night sky, about the stars draped over darkness. “These things are not for you to know,” he’d said, squeezing your tiny fingers too hard. That kind of thing can break you, I’d said. I didn’t need to say it.

The rain had stopped, and the shower and your singing. Messengers of light pushed through the lumpy clouds to the east. The sidewalks were slick brown, dappled in sodden leaves. I felt you behind me. In your hands, the vase of roses.

“Maybe the kitchen,” you said. The silence was the only thing unbroken in the room.

I nodded. There are many things I haven’t told you. A few of them for you, but most of them for me.

When the flowers arrived the day before, something crackled to life between us. You had said, in a soft voice, “Thank you.” Your eyes were on my eyes, not darting above or below. Your cheeks were flushed. Your eyes bright and glimmering.

I didn’t tell you they were not from me.

On the waning petals, a sepulchral wash of color. Outside, reluctant birdsong. We searched the room with our eyes. You were looking for what I could give. I was looking for what I could keep. Beyond us, a million stars. Behind us, only starlight.

—

Jad Josey resides on the central coast of California with his family. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Glimmer Train, Passages North, Pithead Chapel, Palooka, and elsewhere. Reach out on Twitter @jadjosey or online at www.jadjosey.com.

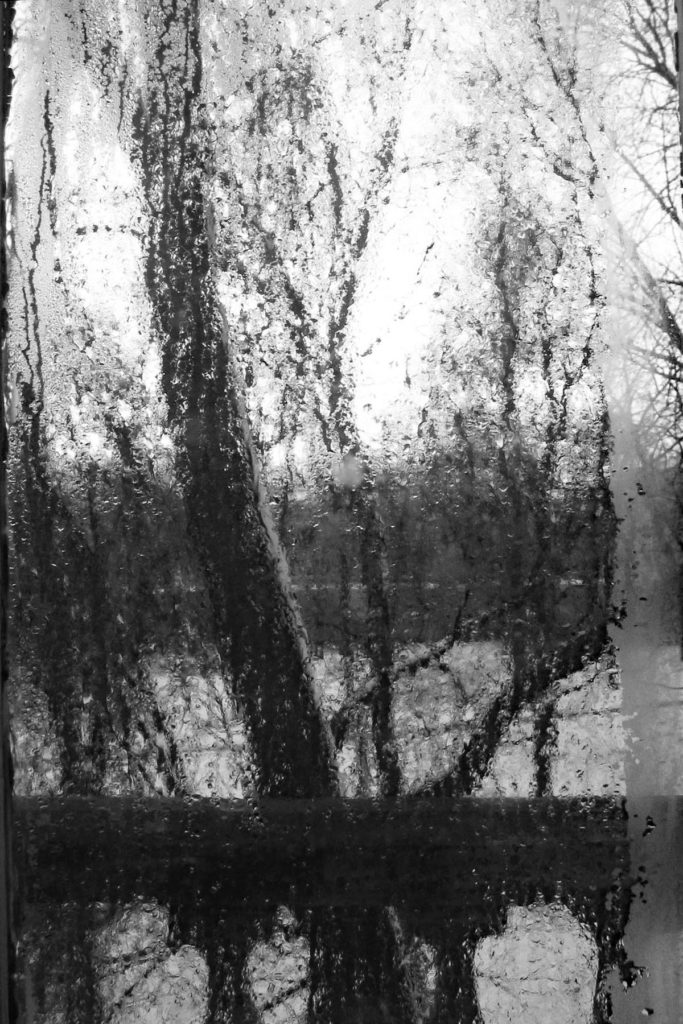

Artwork by: Diane G. Martin

Diane G. Martin, Russian literature specialist, Willamette University graduate, has published work in numerous literary journals including New London Writers, Vine Leaves Literary Review, Poetry Circle, Open: Journal of Arts and Letters, Examined Life, Wordgathering, Dodging the Rain, Antiphon, Dark Ink, Gyroscope, Poor Yorick, and Rhino, Conclave, Slipstream,Stonecoast Review.

Web: www.dianamartin.ru