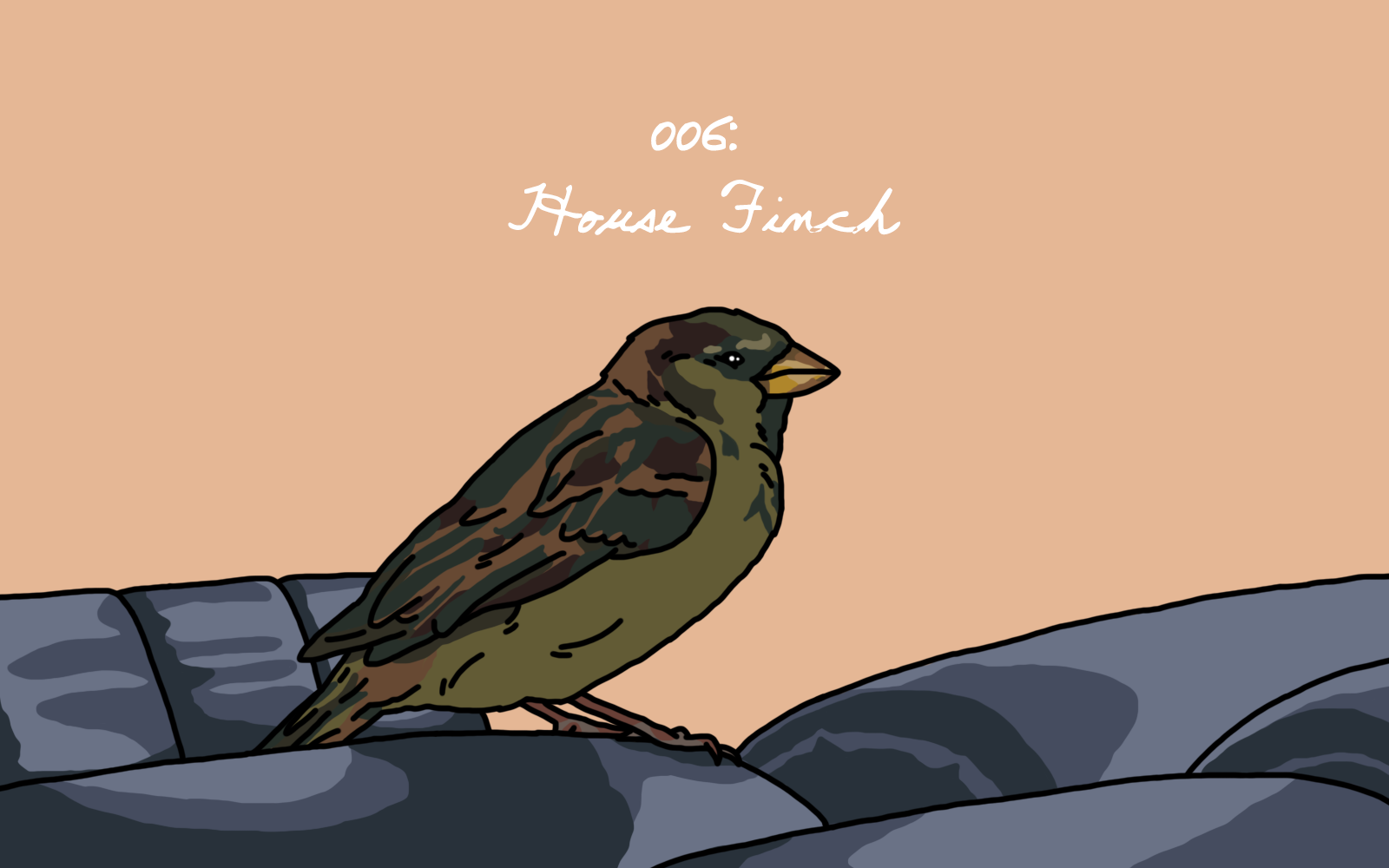

Take the house finch.

But wait: take these two house finches, fluttering around our gate at O’Hare, a rotund mated pair—a female the color of biscuits or café au lait, a male with only the slightest hint of red-mauve on its breast, neck.

It’s early, and everyone is sleep-eyed, waiting for movement, a gate change, information about a flight delay, anything. Outside the vaulted windows, the sky hovers blue-dark, blows violently, a feared and promised storm crawling slow and purple along the horizon, clawing at the peach early morning light, ripping ripping it away.

And yet: here, these two birds flutter, chirp sweetly, hop along the backs of seats, wait for falling crumbs from breakfast muffins and burritos and snack packs of dried fruits and nuts. They’re bold, these finches, but that’s not what grips us: here, they have found some way inside this sprawling airport. Here, there are no seasons, there is food year-round, they are protected from the storm roiling outside.

But no one seems to see them. Or, perhaps: they don’t care about them. Birds they see each and every day, a trivial annoyance fanned away while distracted on their phones, worrying about their final destinations but not, not at all, where they are now.

And such is the story of the house finch, isn’t it? We take them for granted. We see them in splendid numbers at every feeder, crowding dense shrubbery and low-hanging silver maple branches in our yards; everywhere, we see them bounding about, rapid-chirping cheerily. Researchers estimate their numbers to be between 267 million and 1.4 billion—and this, yes, in North America alone.

House finches were originally found in the Western United States and Mexico, set loose on Long Island after a failed venture to brand them as pets (called “Hollywood finches”) proved fruitless. They bred, and spread, and spread, and are now, we know, ubiquitous: we’ve all seen them, all shared a sighting of them. There aren’t many creatures we can say this about, that we have in common like this. Let that sink in.

For instance, take the time we watched two female house finches nibble on a slice of pizza from a take-out container along the side of the road. They took turns: one ate, the other sang, and then they swapped roles, repeated this for some time. It’s an image burned in our brain, one we come back to often: unremarkable birds eating unremarkable food—but that itself is remarkable.

And so, too, these birds in this airport.

Nearby, an old woman breaks off a piece of her sesame seed bagel, pinches it into tiny pieces, and sets it on the empty seat next to her. We watch as the birds, fearless, come to her, eat her food, chirp at her sweetly, then bolt off. Where they go, we can’t know, but through these antiseptic halls they flutter and chase, sing and live, raise young and give grand life to this sterile place.

Everyone else ignores, is preoccupied, yet this old woman, she understands: We don’t need to know what it is they sing about. There is beauty in this ordinary, this everyday, these comings and goings, these shared witnesses to our little lives.

Savor this, won’t you?

—

Robert James Russell is the author of the novellas Mesilla (Dock Street Press) and Sea of Trees (Winter Goose Publishing), and the chapbook Don’t Ask Me to Spell It Out (WhiskeyPaper Press). He is a founding editor of the literary journals Midwestern Gothic and CHEAP POP. You can find his illustrations and writing at robertjamesrussell.com, or on Twitter/Instagram at @robhollywood.

Artwork by: Robert James Russell