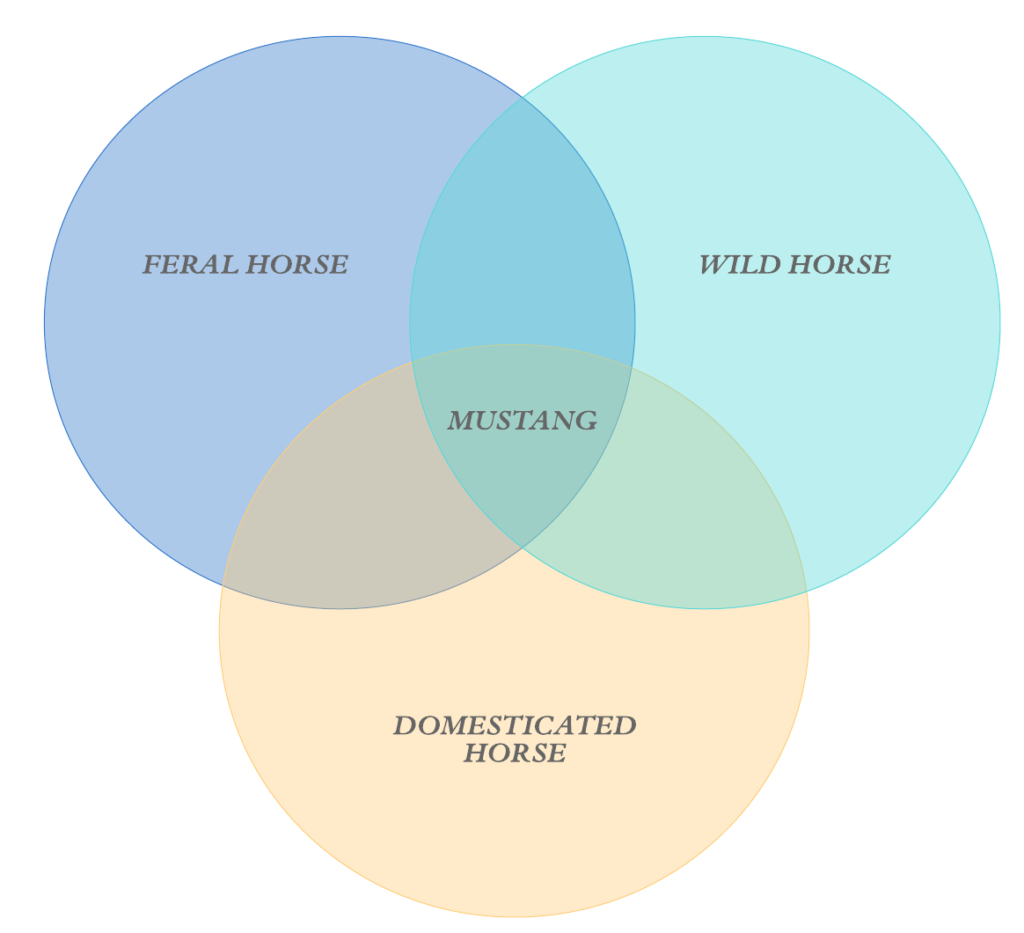

Mustang = a free-roaming horse of the Western United States, descended from once-domesticated horses; defined now as feral horses; may be tamed (see: Domesticated Horse)

Feral Horses = a free-roaming horse of domesticated stock, not a wild animal (e.g. an animal without domesticated ancestors); and yet, some populations of feral horses are managed as wildlife and referred to as “wild”

Wild Horses = a specific species of the genus Equus, and yet also colloquially used to reference free-roaming herds of feral horses (like the mustang) in the United States

Domesticated Horse = domesticated since ancient times, used for riding and/or carrying loads; completely dependent on humans

So, then, this: Clear? Does that help?

Further, then: Horses are divided into three categories depending on their temperment:

Clear? Does that help?

Further, then: Horses are divided into three categories depending on their temperment:

Get it?

So which are you?

You’re in northern Michigan. You’re eighteen, just after high school, at a cottage your family rents. You bring your girlfriend, a year younger than you, though you know you no longer want to be with her, but you’re too afraid to end things (too afraid of everything, of going to college and college parties and meeting new people and not meeting new people and losing the people you’ve had in your life all along). You suggest horseback riding in the woods. She complies, you comply, and your horse, Buttermilk, doesn’t like you and your frivolous compliance with life and tries to buck you but your iron grip (a symptom of fear) keeps you in the saddle, so then Buttermilk sprints, gallops, making scared sounds, snorting wildly, trying to remove you from her. The guide catches up and puts himself and his horse Frank in front of your path, manages to slow you and Buttermilk down, calls you names like pussy and asshole as you’re led back (slowly) to the stables, tells you not to come back ever again.

We could talk, yes, about the Assateague Horse (known also as the Chincoteague Pony), a feral breed that, as legend goes, descended from horses that survived shipwrecks of Spanish galleons, navigated to islands off the coast of Maryland and Virginia, propagated and thrived on salt-marsh plants, ponds of fresh water, not a predator to be found. About the annual pony penning event, where one of the two herds swims from Assateague Island to Chincoteague Island, where they’re allowed to graze, where ponies are later put up for auction on the last Thursday in July. How spectators come, amazed, how a thing that’s survived so furiously can be so easily traded as commodity.

You’re in Costa Rica, you’re in Hawai’i. It’s with the same girl, both times, in college both times, and it’s irrelevant, really, because you were done with each other for so long that the only thing you keep from these memories is the pure joy of the trot, the saline wind, the palm trees and thick greenspace at your back, the sounds of howler monkeys and bullet ants and jungle things alive in every nook, a symphony that mocks how dead your relationship is, constant reminders of what else is out there in the world, a sunset lighting the sky like pineapple rings, like mangoes, like orange glitter and neon-lit signs saying WE’RE CLOSING, WE’RE CLOSING, WHERE’LL YOU GO NOW?

The Tremendous Machine, Secretariat, one of the greatest racehorses of all time, had an abnormally large heart: 22 pounds, or 2.5 times the size of an average horse heart. Dr. Thomas Swerczek, who performed Secretariat’s necropsy, called it a “beautiful engine.” Experts refer to this genetic condition of the oversizing of the heart as the “x-factor,” supposedly passed down from Eclipse, a racehorse who died in 1789, giftingthe trait to his daughters, down down the dam line, pumping massive amounts of blood, circulating oxygen like an industrial air conditioner, almost as if they’d be able to break the bonds of domestication, return to some wild state of freedom, if they ran fast and hard enough.

In fifth grade, a girl named Elaine draws you horses, leaves them inside your flip-open desk when you’re not looking. You’ve never seen a horse up close before, just pictures in books and in the old Technicolor cowboy movies always playing in the background on the living room television. The ones she draws are misshapen, with too-long legs and ovoid heads and rabbit ears and black, colored-in manes with thick, beautiful braids that nearly drape to their knees. At first, they’re just the horse, and then she starts adding portraits of herself riding, with hearts and shooting stars and all the cartoony accoutrement of love beaming out from her head, the horse always in mid-trot with no scenery depicted, a wholesome trip into the barren, blank-paper countryside. Eventually, her rider meets up with one that looks like you, your gangliness and bowl-cut and buck teeth with the space between them. You remember the last one she ever drew you, toward the end of the school year: you’re walking your horse, and she’s nowhere in sight. Your face has no mouth, just two small sunken eyes and hair that doesn’t look much like yours at all, come to think of it. But it’s the horse you can’t stop staring at, its expression: pained, looking off in the distance, a melancholy look of wishing, maybe, it was somewhere else altogether. This drawing, you keep.

Get it?

So which are you?

You’re in northern Michigan. You’re eighteen, just after high school, at a cottage your family rents. You bring your girlfriend, a year younger than you, though you know you no longer want to be with her, but you’re too afraid to end things (too afraid of everything, of going to college and college parties and meeting new people and not meeting new people and losing the people you’ve had in your life all along). You suggest horseback riding in the woods. She complies, you comply, and your horse, Buttermilk, doesn’t like you and your frivolous compliance with life and tries to buck you but your iron grip (a symptom of fear) keeps you in the saddle, so then Buttermilk sprints, gallops, making scared sounds, snorting wildly, trying to remove you from her. The guide catches up and puts himself and his horse Frank in front of your path, manages to slow you and Buttermilk down, calls you names like pussy and asshole as you’re led back (slowly) to the stables, tells you not to come back ever again.

We could talk, yes, about the Assateague Horse (known also as the Chincoteague Pony), a feral breed that, as legend goes, descended from horses that survived shipwrecks of Spanish galleons, navigated to islands off the coast of Maryland and Virginia, propagated and thrived on salt-marsh plants, ponds of fresh water, not a predator to be found. About the annual pony penning event, where one of the two herds swims from Assateague Island to Chincoteague Island, where they’re allowed to graze, where ponies are later put up for auction on the last Thursday in July. How spectators come, amazed, how a thing that’s survived so furiously can be so easily traded as commodity.

You’re in Costa Rica, you’re in Hawai’i. It’s with the same girl, both times, in college both times, and it’s irrelevant, really, because you were done with each other for so long that the only thing you keep from these memories is the pure joy of the trot, the saline wind, the palm trees and thick greenspace at your back, the sounds of howler monkeys and bullet ants and jungle things alive in every nook, a symphony that mocks how dead your relationship is, constant reminders of what else is out there in the world, a sunset lighting the sky like pineapple rings, like mangoes, like orange glitter and neon-lit signs saying WE’RE CLOSING, WE’RE CLOSING, WHERE’LL YOU GO NOW?

The Tremendous Machine, Secretariat, one of the greatest racehorses of all time, had an abnormally large heart: 22 pounds, or 2.5 times the size of an average horse heart. Dr. Thomas Swerczek, who performed Secretariat’s necropsy, called it a “beautiful engine.” Experts refer to this genetic condition of the oversizing of the heart as the “x-factor,” supposedly passed down from Eclipse, a racehorse who died in 1789, giftingthe trait to his daughters, down down the dam line, pumping massive amounts of blood, circulating oxygen like an industrial air conditioner, almost as if they’d be able to break the bonds of domestication, return to some wild state of freedom, if they ran fast and hard enough.

In fifth grade, a girl named Elaine draws you horses, leaves them inside your flip-open desk when you’re not looking. You’ve never seen a horse up close before, just pictures in books and in the old Technicolor cowboy movies always playing in the background on the living room television. The ones she draws are misshapen, with too-long legs and ovoid heads and rabbit ears and black, colored-in manes with thick, beautiful braids that nearly drape to their knees. At first, they’re just the horse, and then she starts adding portraits of herself riding, with hearts and shooting stars and all the cartoony accoutrement of love beaming out from her head, the horse always in mid-trot with no scenery depicted, a wholesome trip into the barren, blank-paper countryside. Eventually, her rider meets up with one that looks like you, your gangliness and bowl-cut and buck teeth with the space between them. You remember the last one she ever drew you, toward the end of the school year: you’re walking your horse, and she’s nowhere in sight. Your face has no mouth, just two small sunken eyes and hair that doesn’t look much like yours at all, come to think of it. But it’s the horse you can’t stop staring at, its expression: pained, looking off in the distance, a melancholy look of wishing, maybe, it was somewhere else altogether. This drawing, you keep.

(c) South Bend Tribune

A stripmall in Indiana has a lifesize, anatomically correct cowboy/horse statue at the entrance, a dark chestnut stallion by the looks of it (or it could be the original paint’s been rubbed off over decades of wear and rainstorms and snow and ice and wind). Every time you go grocery shopping, you pass by it, wonder, wish you were somewhere riding, somewhere out West. So you read up, much as you can, about wild horses, about mustangs. Cowboys and horses: intrinsically linked. Every movie, every cowboy novel, the horse has a name, they’re cared for, loved, mourned when they’re gone. Point, then: the Western, as genre, does not exist without horses. You read about bronc busters, men brought in to break a horse, to domesticate it. They’d tie it down, saddle the horse, tire it out and get on, get on, keep getting on until they let the rider ride. Or cowboys’d tie it to a tree and let it graze for hours, until full and tired, with hardly any fight left. The goal, regardless of the method, is the same: breakage. And this cowboy wisdom plucked from the ether:The trick is to keep getting back on until the horse gets bored.

[cue laughter] Or, how about creasing, a bygone method of capturing wild horses in the American West: a cowboy’d shoot his rifle and try, best he could, to hit the mustang in the neck, just below the ears, about an inch close to the spine, rendering it shocked; not killing it no, but the horse would fall over and the cowboy would run on up, bind it, lead it home. Noteworthy, though: for every one captured by this method, fifty others were killed. You dream of one day having an all-black horse named Tulip, living on some lush forested plot in the northern lands, emerald in all directions, slight hills, perhaps, pine and cedar aroma smacking you whenever you step outside. In this fantasy, you and Tulip slow-trot daily, lazily watching whipped clouds overhead, while buzzing biting things pollinate flowers and fruitbuds and grasses. You move as one. And this, on top of an animal, makes it more organic, your experience—you’re accepted in this way as opposed to trudging on your own two hapless feet, the pair of you, this righteous brew. An escape, whenever you need it, to this wildworld. What’s left?

Classified as a nuisance, mustangs roam open expanses of the American West that are, quickly, becoming less open, closed off by land grabs and new boundaries being drawn. Detractors say they trample precious earth, banks of streams and ponds, that they foul clean water, that they need too much to eat, six million pounds more than what’s available to them on the open range, leaving little for other animals, changing the landscape with their immense appetites—perhaps the most American thing about this animal.

And oh, their intelligence: without question, they’re cognitively superior, deep thinkers, eyes full of wit and wisdom, whole solar systems on display in their pupils. They form strong bonds, remember people decades later, have moods, can count and categorize items, problem-solve, make decisions; they can love.

What’s left?

Classified as a nuisance, mustangs roam open expanses of the American West that are, quickly, becoming less open, closed off by land grabs and new boundaries being drawn. Detractors say they trample precious earth, banks of streams and ponds, that they foul clean water, that they need too much to eat, six million pounds more than what’s available to them on the open range, leaving little for other animals, changing the landscape with their immense appetites—perhaps the most American thing about this animal.

And oh, their intelligence: without question, they’re cognitively superior, deep thinkers, eyes full of wit and wisdom, whole solar systems on display in their pupils. They form strong bonds, remember people decades later, have moods, can count and categorize items, problem-solve, make decisions; they can love.

Where were we?

The horse is running at full-speed, the arch of its back unmistakable, hooves raised high, ears perked, mane blowing, slicing through warm wind, scrubland, high desert, jungle. You’re twenty, no thirty, no sixteen; you’re single, no married, no dating: the horse responds to your touch with spasms of its remarkable muscle, by blowing its lips, letting out an imposing roar. It responds to you, the two of you together, this dance along the horizon, the edge of a lake where a marbled sky overhead promises rain, where thunderous green storms promise relief.

Describe a horse running forever.

No: describe how we got there.

—

Robert James Russell is the author of the novellas Mesilla (Dock Street Press) and Sea of Trees (Winter Goose Publishing), and the chapbook Don’t Ask Me to Spell It Out (WhiskeyPaper Press). He is a founding editor of the literary journals Midwestern Gothic and CHEAP POP. You can find his illustrations and writing at robertjamesrussell.com, or on Twitter/Instagram at @robhollywood.

Where were we?

The horse is running at full-speed, the arch of its back unmistakable, hooves raised high, ears perked, mane blowing, slicing through warm wind, scrubland, high desert, jungle. You’re twenty, no thirty, no sixteen; you’re single, no married, no dating: the horse responds to your touch with spasms of its remarkable muscle, by blowing its lips, letting out an imposing roar. It responds to you, the two of you together, this dance along the horizon, the edge of a lake where a marbled sky overhead promises rain, where thunderous green storms promise relief.

Describe a horse running forever.

No: describe how we got there.

—

Robert James Russell is the author of the novellas Mesilla (Dock Street Press) and Sea of Trees (Winter Goose Publishing), and the chapbook Don’t Ask Me to Spell It Out (WhiskeyPaper Press). He is a founding editor of the literary journals Midwestern Gothic and CHEAP POP. You can find his illustrations and writing at robertjamesrussell.com, or on Twitter/Instagram at @robhollywood.

Artwork by: Robert James Russell

Artwork by: Robert James Russell