The Sky is a Story: A Lesson With Robert James Russell

Introduction

This is not, dear reader, really a lesson about describing the sky (although, yes, we’ll do just that); rather, this is a lesson about descriptive, imaginative writing, stretching our limits as writers, not giving into cliché (that old albatross).

Bear with me, will you?

Description + Perspective

In The Art of Description (a book I re-read a few times a year, draw endless inspiration from, and can’t recommend enough), Mark Doty writes,

“When we repeat the familiar phrase that something is ‘beyond the pale,’ we’re employing what Donald Hall has called a dead metaphor, using a comparison we don’t even notice anymore because it’s become a cliche or because the vehicle it employs to make meaning has lost its significance in contemporary speech. ‘Beyond the pale’ means to go outside the fence, though I doubt there’s a living speaker of English who thinks of a fence as ‘a pale.’

What this lesson will (hopefully) get you to do is consider the words we, as writers, choose. Or, perhaps, maybe it’s this: think about what your default is, the crutches we all have—in word choice, but also genre, form, content, perspective and POV.

I will always, always, heed the idea that writing should be hard work. Sure, there’ll be moments of fluidity, times when we can’t even fathom how quickly we’re putting proverbial pen to paper, but especially when we’re starting out, we should be asking these kinds of tough questions: Why am I writing the way I am? Why am I using these words? How am I pushing myself?

We digress. Back to the sky.

The beautiful thing about the sky is that it’s different to each of us, reminds us each of some unique thing, a memory, an experience, a place, colors we see in a way no one else does. (We’re skirting the line here of relativism, so bear with me.) Again, Mark Doty:

“In fact all perception is limited, no matter how acute your eyesight, how sharp your hearing, how sensitive the sense of touch.”

Yes, yes. So when I look up and see the sky, depending on my day (or my mood, how work went, what I had for dinner, if I’m squabbling with anyone, etc.), or ever so slight shifts in my position (if I’m within my car, by a window, standing in an open field), even if we see the same sky, we might view it completely (and splendidly) differently.

One last Mark Doty quote:

“What is memory but a story about how we lived?”

So, when we describe anything, we’re speaking figuratively, because we can’t literally, or actually, describe what any of us are experiencing.

What I want you thinking about is all the little things that make you who you are, on any given day, and how we lean into our words when we write. It’s hard to come up with new ways to say something, and the sky—and/or the weather—is a great place to start.

Why the Sky?

The sky is universal. We go outside (or don’t) depending on the weather. With strangers, we talk about the weather. We take snapshots of the sky when it blushes mauve, or when it’s readying for a downpour and steels over. It’s the one thing we all have in common (how we interact with it, how it allows us to live our lives or impedes us from doing so). We all, in fits of melancholy and love and hope and hopelessness and awe, look up at the sky. Maybe we’re looking for an answer? Maybe we just want to make sure we’re all still here? Regardless, it’s what we do, all of us.

Hemingway, who may have been wrong about many things in his life, was right, at least, about this:

“Remember to get the weather in your god damned book–weather is very important.”

Indeed. And for our purposes, the simple exercise of “Describe the Sky” is a great exercise, a simple in. The sky (and/or the weather) can do many things in a narrative. It can be world-building, mood-setting, can drive the story forward (or backward). It can be symbolic, affect the plot and character motivations.

Yes, we should be thinking about sensory details in what we write, but descriptive writing can be more than colors and comparisons to objects (although, sure, these can be wonderfully relevant). Good descriptive writing takes advantage of figurative language, is an invocation: what are you sensing about this place, this sky, this weather? What, beyond the typical (the expected), can you tell us about what you’re envisioning? The bonus of going the extra mile in your descriptive language is, as you’ll see in a few examples below, you can give us less and yet have it be more.

Not every detail needs to be bloody-knuckled over such that you sweat bullets to find perfectly-new language for every single word and scene. That’s impossible and not necessary. But how much of your writing is habitual, and how much are you pushing yourself and your narrative to try something new? The sky can be your litmus test, a barometer of your creative process. What are you putting in? What are you phoning in? Are you letting yourself get away with being lazy? What could you change, right now, even in a few small, key places, to wildly shake up everything?

I believe in you. I turn to the sky―and nature in general―because I love being struck dumb by the awesomeness of the natural world. Clear days, raging storms, explosive wind, neon green plants that shoot up in the sidewalk cracks, a hover of pigeons living beneath the overpass, how the world moves on, continues its show always, forever. This is hope.

Lean into this, my friends: every day is different. The sky, even if it looks the same as the day before, brings with it something new every new day, doesn’t it? And we ascribe new values and feelings and emotions to it. It’s what we do, and it can be an endless source of inspiration, if you’ll let it.

Samples

There are countless beautiful, awe-inspiring lines written about the sky. Here’s one I love from Haruki Murakami:

“The sky grew darker, painted blue on blue, one stroke at a time, into deeper and deeper shades of night.”

He doesn’t reinvent the wheel, this isn’t baroque for the sake of baroque, but he goes behind just telling us: “It got dark.”

Maybe the sky, for example, is clear-blue, or cloudless, but telling us the “sky is clear-blue and cloudless” is as if you’re telling us nothing. We feel nothing. There’s nothing to process here. Reach back: the neon color of a clear July sky is going to remind you of something: is it a picnic sky? A sunburned face and greasy fried chicken sky? Is it the topaz of a brooch your grandma used to wear?

Catch us off guard. Throw us for a loop. Think critically as you read others’ work–how do they accomplish this?

Some other examples I love:

“Elsewhere the sky is the roof of the world; but here the earth was the floor of the sky.”

―Willa Cather, Death Comes for the Archbishop

“So fine was the morning except for a streak of wind here and there that the sea and sky looked all one fabric, as if sails were stuck high up in the sky, or the clouds had dropped down into the sea.”

―Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse

“He lay on his back in his blankets and looked out where the quartermoon lay cocked over the heel of the mountains. In the false blue dawn the Pleiades seemed to be rising up into the darkness above the world and dragging all the stars away, the great diamond of Orion and Cepella and the signature of Cassiopeia all rising up through the phosphorous dark like a sea-net. He lay a long time listening to the others breathing in their sleep while he contemplated the wildness about him, the wildness within.”

―Cormac McCarthy, All the Pretty Horses

“Oh, God, make small

The old star-eaten blanket of the sky,

That I may fold it round me and in comfort lie.”

―T. E. Hulme, ‘The Embankment’

“[…] making up our rassoodocks what to do with the evening, a flip dark chill winter bastard though dry.”

―Anthony Burgess, A Clockwork Orange

See what they do? Each description is unique, fits the narrative, figuratively goes for it, doesn’t it? The sky is never just the sky, the sky is a complex web of emotions, of perspective, of sensations, and, depending on who’s seeing it, who’s narrating who’s seeing it, it should be more complex. The sky is a story.

Sure, not every piece we write needs to go into great depth about the sky, the weather, the ground beneath our characters’ feet. But again, it’s a good practice mechanism that you can scale outward: How is this character seeing the world? What words am I, the writer, relying on, to get this unique POV across?

Other Inspirations

Last, before our prompts. I also find great inspiration from visual art when I research ideas, think about descriptions, try to find new metaphors for the things we see around us every day. My favorite are abstract expressionist paintings that allow us, the viewer, to craft whatever narrative we see fit. A few examples:

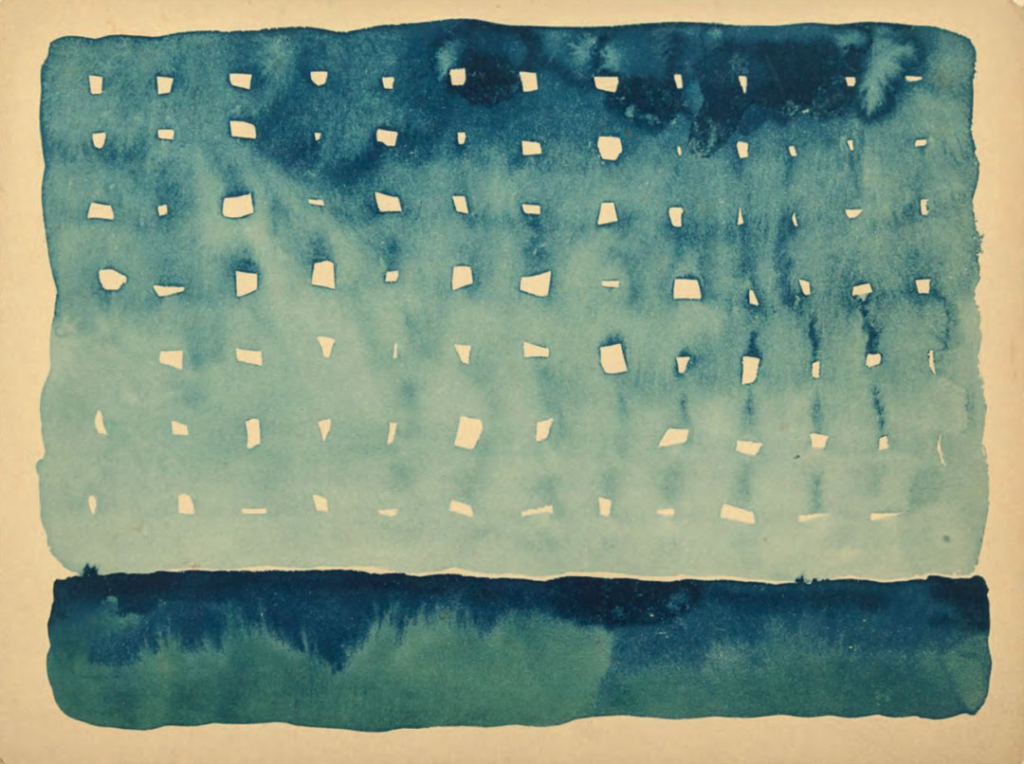

This first one is by Georgia O’Keeffe, called “Starlight Night” (1963):

And another by O’Keeffe, “Sky Above Clouds IV” (1965):

And one more, Willem de Kooning’s “Rosy Fingered Dawn at Louise Point” (1963):

Prompt #1: No Color

I want you to look out your window, right now. Look at the sky, the clouds, the colors, the shapes of everything you see, the flow. If there’s rain, what direction is it coming from? If it’s sunny, what color is the light? Heck, what color is the sky, but think about it in relation to physical objects: gray like _____, blue like _____, etc. Or maybe its size―does it go on forever? Does it seem cluttered or small? Does it seem to blend into the horizon, or be sprung from it?

Look at your sky for five minutes. Study it. Absorb it. Let your eyes wander, drift like the clouds, but make sure to take it all in, best you can.

Now, I want you, in a sentence, to describe the sky without using color at all. What feeling do you get? If you were writing a story set here, and now, with you, the character, looking at this sky, what would you write? Give us something we haven’t seen before, a metaphor that you’ve never used or read to describe the sky, imagery that simultaneously shakes our foundations of what good writing can do while still seeming familiar―that gives us a way in, still allows us to get it, in the end.

For instance, it’s near-rain here, so I might say, simply: The sky is a fist.

That might be enough. That might be all you need. What can you tell us in a sentence?

Prompt #2: With Color

The same sky, right now. Look at it again.

If it’s shifted or changed, great. If it’s the same, push yourself here. I want you to describe the sky using color(s) but also other figurative and descriptive language, as needed. We want color that portends more than just the word, description that helps paint a scene, or a character’s place at that moment. Remember: sky as story.

Simple color can work paired with more (again, a “blue sky” is something we’ve seen countless times and, quite frankly, on its own, is meaningless, but think back to Murakami’s “painted blue on blue” to describe the coming dark), but don’t be afraid to go further: is the sky the color of biscuit dough? The color of the culvert that ran under the road by your crumbling middle school back home?

Here’s a few of mine from a recent project, not because they are crème de la crème, but because I, too, play this game regularly:

Outside, it’s too early for twilight, but the sky purples and darkens anyway.

He’s pacing near the front window, then walks to the fire and warms his palms, touches them to his cheeks, then is back at the window again watching the rain let up, the sky break through in yellow spears of heaven-light.

The sky behind them is chalky, resinous, portending rain or doom.

So, in a sentence, describe the sky using color but in an unexpected way, in a way that gives us more than what’s actually being said, that helps us see further than we might be able to otherwise. That gives us more than a scene or an image, but a feeling, a sensation, a story.

Can’t wait to see what you come up with, and I hope you’ll share it with me (and Pidgeonholes) on social media. After all, as Emerson wrote, “The sky is the daily bread of the eyes.”

—

Robert James Russell is the author of the novellas Mesilla (Dock Street Press) and Sea of Trees (Winter Goose Publishing), and the chapbook Don’t Ask Me to Spell It Out (WhiskeyPaper Press). He is a founding editor of the literary journals Midwestern Gothic and CHEAP POP. You can find his illustrations and writing at robertjamesrussell.com, or on Twitter/Instagram at @robhollywood.