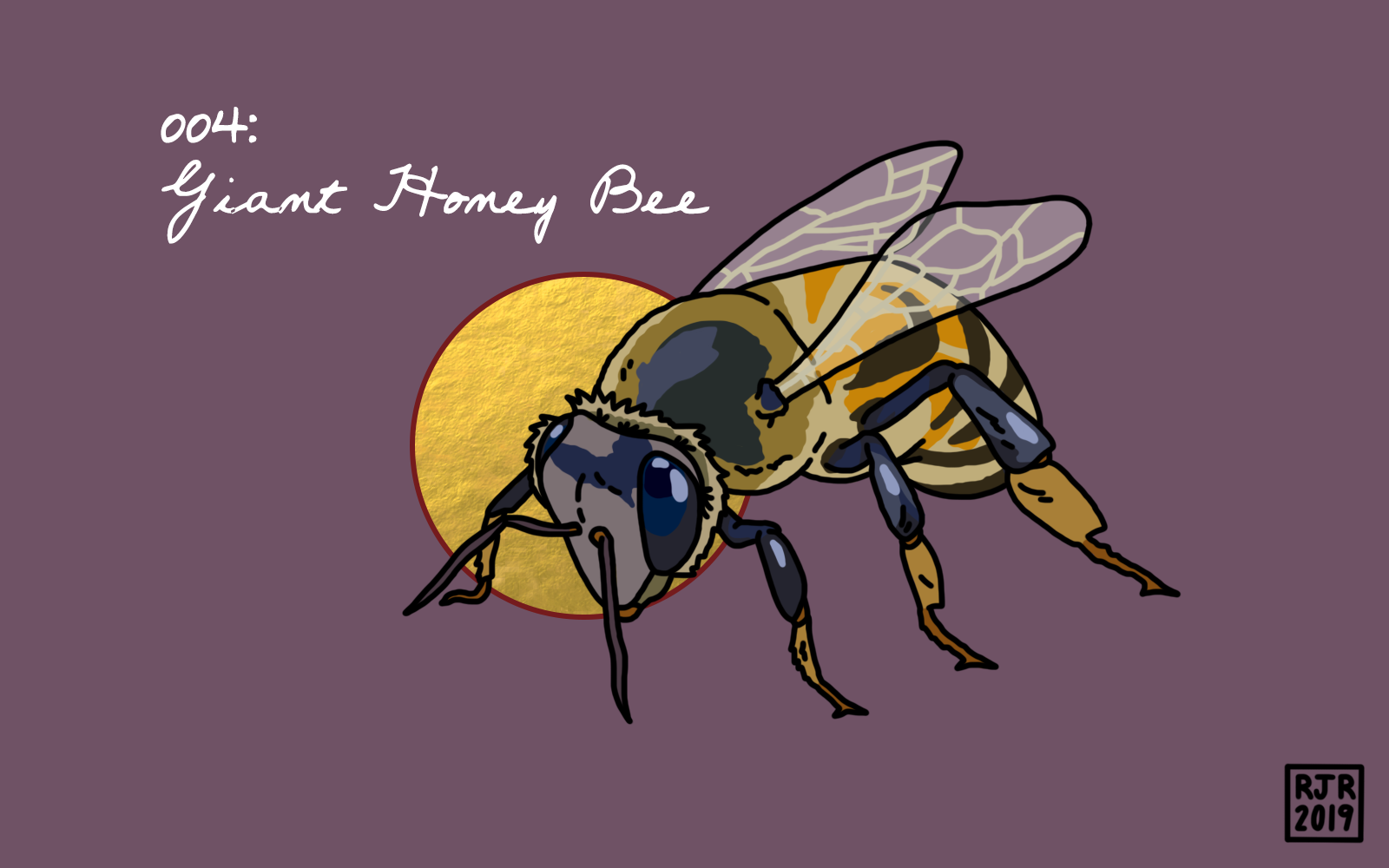

Take the giant honey bee.

We’re not talking about how honey bees’ cross-pollination helps 90% of wild plants thrive; that without them, important crops like persimmon, cardamom and cotton, apricot and sweet cherry, lima bean and coffee, would die off.

We’re not talking about the ancient activity of honey harvesting—how you can find the act depicted on an 8,000-year-old cave painting in Spain, rust-red smears along the rock showing a human climbing, hands in the hive, bees circling, circling.

No, we’re talking about the giant honey bees’ shimmering defense meant to disorient and ward off predators like hornets, unable to land on the now-moving surface, forced to seek sustenance elsewhere.

Having trouble picturing? It’s an undulating wave, a pulse. It’s a magical-shining pattern, and we know how it works, we do: the bees flap their wings up like a crowd-wave at a baseball game, show their dark bodies, create a wave-like movement, a pattern of rings and bursts that moves outward, stops, starts back up again, neatly throbs, throbs.

Thousands of bees in sync, desperate to protect. Every single honeybee acts as a part of a larger whole, moving in unison, no one out of turn.

It’s the heartbeat of the colony, maybe.

It’s so easy to think of bees, of all bugs, as blank-eyed creatures here to annoy or sting or frighten, existing on the periphery of social comfort, a reminder of our days in the wild. We’re past that now, we think without saying aloud. We built shelters and roads and communities and are above those things that creep, that crawl.

And yet: these are the beings we know so little about but depend on so much. Spiders eat the disease-ridden that invade our homes; beetles and ants decompose along the forest floor, allowing growth, allowing room for spring saplings to move up toward the light. They’re food sources for our food sources.

So, that is our working theory: bees shimmer along the hive to ward off, to protect (as opposed to stinging, to dying, to that potentially mortal defense). But we just don’t know—can’t know, can we?—the full implications: what it is they whisper to one another, this throbbing message sent in nanoseconds, sent near the speed of light, means, or how it’s interpreted by a world we’re convinced we’re above.

It’s a neural network.

It’s a beautiful global consciousness.

Oh, god, how little we know about what’s beneath our feet or flying over our heads, how we run from understanding, the secrets of the universe buzzing around us, all that it could impart if we’d just stop and listen for a while.

If we’d just stop.

—

Robert James Russell is the author of the novellas Mesilla (Dock Street Press) and Sea of Trees (Winter Goose Publishing), and the chapbook Don’t Ask Me to Spell It Out (WhiskeyPaper Press). He is a founding editor of the literary journals Midwestern Gothic and CHEAP POP. You can find his illustrations and writing at robertjamesrussell.com, or on Twitter/Instagram at @robhollywood.

Artwork by: Robert James Russell